Anton Räderscheidt

Joseph Haubrich

The painter of the New Objectivity

1889-1961

Josef Haubrich – a life with art “My experience from 40 years of living with art: I have almost never regretted having acquired a work of art, but I have sometimes regretted not having acquired one for years.”

Joseph Haubrich

Alice and Joseph Haubrich, 1931

Oil on canvas

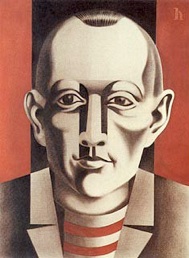

Anton Räderscheidt

Portrait Joseph Haubrich

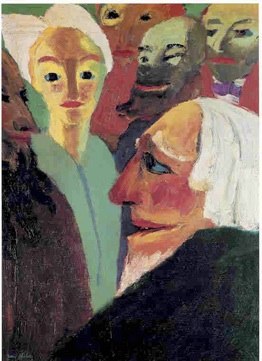

Heinrich Hoerle

Josef Haubrich is “the” personality of the exciting post-war years in Cologne, which was mainly characterized by an unbelievable pent-up demand for art and culture. He was part of the scene around the Denant wine house and has a lasting impact on Cologne’s cultural landscape. On June 15, 1889, Ludwig Josef Haubrich was born into a middle-class family in Cologne, the son of a director of the local health insurance fund. He grew up in a rented apartment at Mühlenbach 37. Later the family bought one of the first houses in the new Klettenberg district at Hardtstraße 19. In 1907, Josef Haubrich graduated from high school in Kreuzgasse. The family was quite artsy. In the cathedral lottery, the father was responsible for the selection of the paintings that were awarded as prizes and here the early roots of Josef Haubrich’s enthusiasm for art can be seen. However, his father’s taste in art, which he was often allowed to accompany on trips abroad, was well adapted to the established directions and Josef Haubrich, too, had developed an enthusiasm for 19th century genre and history paintings in his younger years. In spite of all his knowledge and preoccupation with the art world, it is logical that he began studying law in 1907. In the winter semester he is drawn to Munich. The city, however, gave him further fodder for his interest in art. Numerous galleries, imposing museums and interesting circles of artists were his home for the next few years and continued to shape his artistic sense. However, he purposefully completed his law degree and wrote a doctoral thesis entitled “The discounting of accounts receivable”. His goal for the future was: industrial lawyer. A cleverly chosen branch of law, as this was where most of the work was to be expected in the mood of optimism in the post-war period. However, Josef Haubrich initially started a traineeship at the local court in Lindlar.

Au rendez-vous des amis (Meet up with friends), 1922

Oil on canvas, 130 x 195 cm

Max Ernst, Museum Ludwig 1976

Joseph Haubrich and Mother Ey infront of Max Ernst picture

Foto Hannes Flach Vintage

Josef Haubrich had also followed the development of the Wallraf-Richartz-Museum with great interest, in which the director at the time, Alfred Hagelstange, ensured that there was a connection to the modern age. In 1912 he bought the “Bridge of Arles”, which Vincent van Gogh had painted so often under the influence of the southern sun. The donation of the Seeger Collection with numerous pictures by the realistic painter Wilhelm Leibl also paved the way for the new pictures. All of this met the taste of Josef Haubrich and he made many visits to the museum. Nevertheless, one must not forget that in 1912 more revolutionary artists appeared on the scene and they had to be discovered. The “International Art Exhibition of the Sonderbund of West German Art Friends and Artists in Cologne 1912” – in short “Sonderbundausstellung” – offered the opportunity to do so. From May 25 to September 30, the leading museum directors and gallery owners in Germany (in addition to Hagelstange, above all Karl Ernst Osthaus as well as Flechtheim and important art collectors) presented in Cologne what modern art movements had developed over the years since the turn of the century. “That the relationship between the new Cologne and modern art will be as intimate as that of the old one with the art of its time, the Sonderbund would like to contribute to its part,” was the statement at the time. The official Cologne in the person of the then mayor Max Wallraf complained, however, that the exhibition had incurred the wrath of the emperor, who, as is well known, had a very unique conception of what art was. “An art that defies the laws and barriers I have described is no longer art, (…).” For art-loving people like Josef Haubrich, however, the exhibition was a revelation. 108 van Goghs, 24 Cézannes, 21 Gauguins, 32 Munchs as well as pictures by Picasso, Matisse, Marc, Kandinsky, Jawlensky, Klee, Kokoschka, Nolde and many other young painters opened up a completely new world for him.

1952 v.l. Dr. Schmidt-Rost, Frau Bamann, Anton Räderscheidt, Dr. Joseph Haubrich in the

Cologne Art association

Heinrich Hoerle 1929

oil on canvas, 68,5 x 95,5 cm

Collection Haubrich 1946

“The exhibition was launched yesterday with the commanding generals and mayors. Picasso! Picasso! Picasso! “, Jubilated Macke in a letter to Marc. Josef Haubrich enthusiastically accepted all the suggestions of young art and this fire got even more tinder when in 1914 the Werkbund exhibition on the exhibition grounds set another milestone in modern art awareness in his hometown. In order to develop good taste, a wide variety of work groups showed their skills here. The famous glass house by Bruno Taut, for example, was trend-setting and has an impact on modern architecture to this day. This event also made a lasting impression on the young Josef Haubrich and he took a lively part in the development of new directions in applied arts and architecture. This spirit of optimism and enthusiasm for modernism was suddenly interrupted by the outbreak of the First World War, which many of the impetuous young artists had greeted as a cleansing storm. The experience of death and devastation that this war was to bring has not yet been had. And so it is not surprising that a large number of the coming experiences experienced a shock that could hardly be overcome, which made the production of art no longer possible. Leading figures such as August Macke and Franz Marc fell at the beginning of the war, Ernst Ludwig Kirchner had to be admitted to a mental hospital and others were barely able to process what they saw. After a short grace period, Josef Haubrich was also called up for his exam in 1916 and he had to come to Berlin for a draft. The stay there dragged on and so he had plenty of time between all the drafting appointments to look around in the local art scene, which with the legendary Herwarth Walden, one of the fathers of the Expressionist movement, had to offer. Josef Haubrich visited a memorial exhibition for Franz Marc, who died near Verdun, and purchased his first sculpture: a figure that Lehmbruck had worked during his time in Paris. The young lawyer had very courageously invested a few hundred marks for this work, fully aware that he might find little understanding from those around him. Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s art was too modern and new precisely because the sculpture seemed difficult to break away from the classic models. Haubrich’s stay in Berlin came to a happy end: because of a heart defect, he was retired and was now able to marry his love Johanna Kux on May 25, 1916 and finally set up a legal practice. He and Hanna moved into a comfortable apartment at Siebengebirgsallee 17.

The destructiveness of the war resulted in a general resignation, which also had an impact on the development of art. Nobody wanted to seriously stick to the classical traditions anymore and Josef Haubrich also gave up collecting established art, which he had practiced on a modest basis until the outbreak of war. He cultivated intense friendships with young painters such as Peter Abelen, Michael Brunthaler, Heinrich May and T.C. Mushroom. He became more and more interested in the dissonant and exciting art of the young, wild expressionists. And when he moved to his house at Eugen-Langen-Straße 29 in Marienburg shortly after the war, one of the most important collections of Expressionist art was to have its place of birth here. Josef Haubrich started to buy. Even with the hard currency, the dollar, which was more popular in times of recession. Since the young art was still relatively cheap (he paid half a dollar for a dix, for example) his collection grew quickly.

In the mid-1920s, however, he also bought two pictures by James Ensor for around 10,000 gold marks, for example: “The girl with the doll” and “Skeleton, looking at Chinese pictures”. That was a huge sum. As a lawyer, Haubrich had become successful and wealthy. So he could afford to live out his passion for collecting. Josef Haubrich moved in circles of artists and collectors in Cologne and his opinion was very important. He saw Alexander Schnütgen as a great role model, who encouraged him to build up a collection in a targeted manner – also with the perspective of making it accessible to the public. In 1923 Josef Haubrich was elected to the board of the Kölnischer Kunstverein and played a key role in its exhibitions. Under the pseudonym Ludwig Josef, he wrote highly regarded art reviews for the “Rheinische Zeitung”. He was a big player in Cologne’s art scene, was there everywhere, knew the most important artists’ get-togethers, such as the Damm tea room on Hohen Strasse or the Monopol café, and visited the studios. At that time, the Denant wine house was also a popular meeting place for art lovers and intellectual greats. “One of the towering pillars at the Denant symposia is of course Doctor Haubrich, patron and collector. His voluminous sanguine appearance is the focus when the latest Cologne jokes are told and benchmarks for the latest works are handed out. ”This is what Fritz Franz Florian wrote later in his delightful“ small instructions for use in a big city ”. Also described there is the most important modern gallery, which was the first point of contact next to the art dealer Karl Nierendorf Haubrichs.

Junge Frau und Männer (Young woman and men), 1921

oil on canvas 101 x 73 cm

Emil Nolde

until 1933 Collection Paul Multhaupt, Düsseldorf

1933 Gallery Alex Vömel, Düsseldorf

1933 Collection Dr. Josef Haubrich, Köln

1946Wallraff-Richartz-Museum acquired through Dr. Haubrich

1976 Museum-Ludwig

Sabbath, 1910

oil on canvas 90,5 cm x 94,5 cm

Marc Chagall

1910 J.B. Neumann, Berlin

1926 Paul Multhaupt Collection , Düsseldorf

1933 Dr. Josef Haubrich Collection, Köln

1946Wallraff-Richartz-Museum acquired through Dr. Haubrich

1976 Museum-Ludwig, Köln

The flashback accurately describes the importance of modern art in Cologne in these years: “A road breakthrough goes west from Neumarkt to the ring. This is where the Ferdinand Möller gallery is located. This is perhaps the most beautiful modern art shop there is on the continent. It was built by the architect Wilhelm Riphahn, honorary doctor, a kind of Cologne Schinkel, not in terms of style, but in terms of rank and influence. Dr. Haubrich, meanwhile, became a meeting point for people interested in art, who often discussed modernity late into the night. In 1922 Haubrich was a widower with two young children. Probably also looking for a mother for the two, he married Dora Anna Amalie Antonie Timmermanns in 1923. The marriage was divorced, however, and in 1929 he married the gynecologist Alice Gottschalk – a Jewish woman with whom he, as a cheerful couple, often formed the center of attention at the legendary artists’ balls. But luck caught up with the course of history and in 1938 his wife was forced to close her doctor’s office. In 1944 she committed suicide in order to avoid being questioned by the Gestapo. Under the impression of private persecution, Josef Haubrich remained loyal to the modern art movement, which was so hated by the National Socialists, despite all the adversities. Because he was married to a Jew, the National Socialists demanded that he leave the Kölnischer Kunstverein. A demand that the Kunstverein never really complied with, and so Haubrich’s influence on the development of the art scene in Cologne remained unbroken. His house emerged as an important center of modernity. Here the paintings were still safe from access by the rulers, who meanwhile sent a commission through the German museums to remove ‘degenerate’ artists. When someone told his chancellor to part with Haubrich, things got tighter for Josef Haubrich. He was now working in his apartment and one day the Gestapo visited him, who eyed the pictures on his walls suspiciously. Since there was still a certain acceptance of French artists at the time, Haubrich came up with a trick: he claimed, for example, that Carl Hofer was French. Charles Hofer! And the Gestapo thugs didn’t have a clue of anything anyway and bought it from him!

In the next few years, however, Josef Haubrich devoted himself more to his work as a lawyer. As a collector, his hands were often tied. Even the beloved Paris trips were hardly possible after the outbreak of war. Towards the end of 1944 he found some consolation in his marriage to Paula Anna Berta Wegelin. The war also left its mark on Haubrich; towards the end his son Karl-Klaus had died. Still, he hadn’t let himself get down. However, the post-war years should not necessarily be easy. Of course, you initially had other concerns than dealing with modern art. But slowly a certain hunger for education, for art and literature grew out of the ruins. And it was quite surprising that Haubrich and his collection were obviously known abroad as well. An American occupation officer, responsible for the field of art, examined the pictures in the collection and hired Haubrich as a lawyer before the military tribunal. When the American front troops were replaced by the British occupying powers on June 21, 1945, the situation worsened for Haubrich and he came under increasing pressure after the confiscation of his private house. That may have been the decisive factor in donating his collection to the city of Cologne. In this way, Haubrich also set a drawing of hope in a city that was destroyed like hardly any other German city. So here you were able to catch up with the spirit of optimism of the early years – with the Sonderbund and Werkbund exhibition, Cologne had risen to become the center for modern art next to Berlin. “Anyone who has seen this collection knows that this is a particularly generous work by an important collector. One can say that not only the foundations of a museum have been maintained here, but that a museum of modern art has been created. ” With these words of Prof. Nipperdey (SPD) in mind on the occasion of the donation, one can understand the disappointment of Haubrich’s daughter, who died a few weeks ago in Argentina, who would have liked to see her father’s name more prominently highlighted in what is now Museum Ludwig. After all, in the redesign of the house after the venerable Wallraf-Richartz Museum moved out, the Haubrich Collection was given a prominent presence. The portrait bust of Haubrich created by Gerhard Marcks also forms a central point at which the biography of the collector and patron is conveyed to the museum public.

In the post-war period, Josef Haubrich played a central role as chairman of the cultural committee in the city council, especially in the construction of the award-winning museum building by Rudolf Schwarz, in which his collection was to be presented in a splendid way from 1957.

Josef Haubrich’s house in Cologne (Architect: Wilhelm Riphahn)

Joseph Haubrichs grave on Melaten

In 1951 he had a house built by Wilhelm Riphahn, which also made clear his claim as an art collector in architecture. A daring rotunda – the so-called Tuskulum – housed all of his pictures and books. “In the house that he had Wilhelm Riphahn – the Cologne architect of the new era – put on the outskirts of the city (Müngersdorf, Kämpchensweg 1), a natural, clear, informal, natural, earthy and natural world lived in form and content material-related benefit. Paintings from his collection greeted the many guests here. His plump, animalistic nature, his alert spirit were the instincts of a sociable addiction to anecdotes and stories. “(Peter Fuchs, Josef Haubrich. Collectors and donors of modern art) Haubrich’s private life took another tumultuous turn when he married Lucy Millowitsch in 1960 as the fifth wife. In 1961 Josef Haubrich died in Bad Münstereifel after a fulfilled life for art. His hometown honored him in 1979 with the naming of the new art gallery, which is now history. So the square next to the Heumarkt, where a great cultural center is to be located in the future, remains in the memory of the people of Cologne of an important co-creator of Cologne’s intellectual life.